“Until the women of Ireland are free, the men will not achieve emancipation.” [Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington, 1909]

Something that keeps coming up in my explorations of Ireland and its history is the prominence of Feminism. I did not know very much about Ireland before coming here, but Feminism being strong in its history was not something I was expecting for some reason; however, I am overjoyed to learn about this part of their history. In Kilfeather’s Dublin: A Cultural History, my trusted companion for my journeys here, there is mention of popular Irish historians wanting to revive the Brehon Laws in the 1880s – 1920s, which were quite egalitarian and “significantly less patriarchal than the imposed British culture.” (pg. 142) Feminist qualities can also be seen in Bram Stoker’s Dracula, which came out in this time of “Irish Literary Revival”, as Kilfeather calls it. I was more quick to judge the anti-feminist aspects of the book until I heard the discussions of some of my peers, who are also with me on this journey in Ireland. They pointed out an important fact: Mina is the brains of the operation. She is quite a dynamic character and proposes what were then bold ideas, like seeing your partner asleep before marriage and the woman proposing to a man – and doing a better job at it! (Stoker 1897: 98-99) Sure, it would be easy to point out the misogynistic aspects of the book, but I think there is due praise for the independence and forward thinking of Mina Murray Harker, especially for the time!

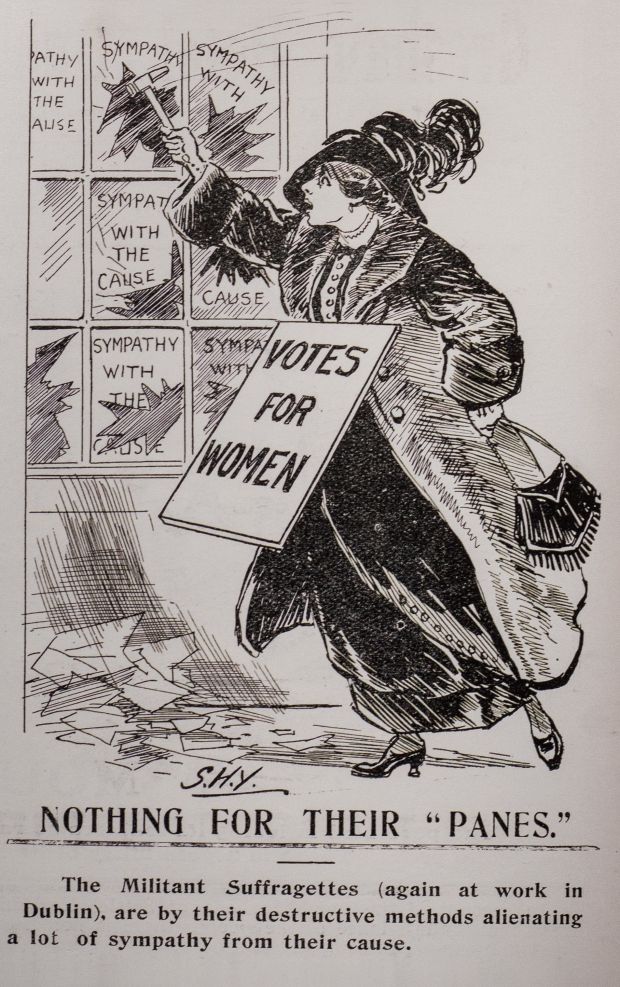

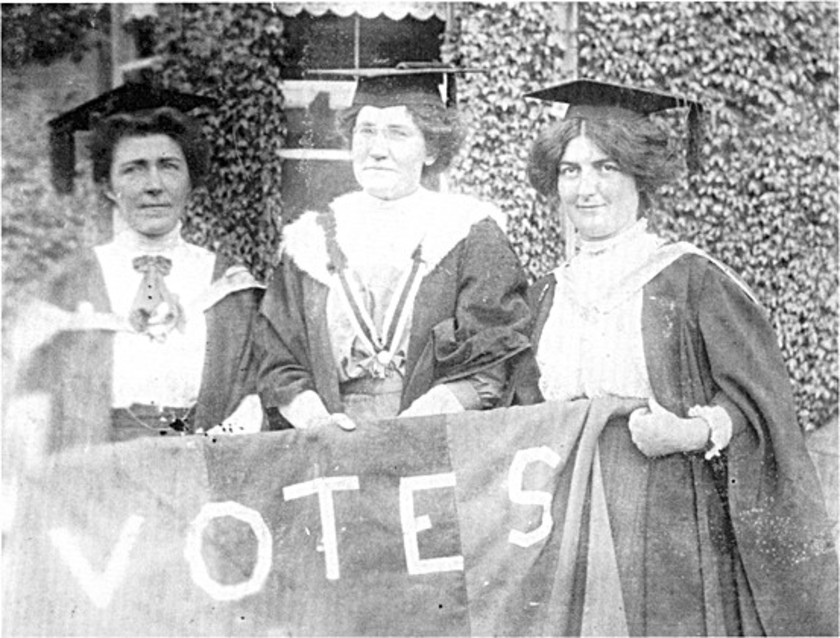

The Suffragettes in Dublin were taking radical steps to get women to be able to vote, even if they weren’t popularly condoned by the public or some other feminist groups. Kilfeather talks about a fiery morning when the Irish Women’s Franchise League protested the vote to leave women’s voting out of the Irish Home Rule Bill of 1912 (pg. 175). They smashed the windows of government buildings, such as the Custom House and Dublin Castle, and got pretty far until they were caught and taken to jail (pg. 175). When they were sentenced to some time in prison, they did a hunger strike, which opened their eyes to the privilege they had been experiencing in their regular lives and now felt a stronger cause for the underprivileged of society (pg. 176). Some other unfortunate events happened later on by radical feminists that tainted the public view of feminism as a whole in Dublin, setting them back even further; regardless, I feel it is important to notice the bravery these early feminists exhibited when they were being stripped of their rights.

I was also very surprised and happy about the strong female presence in Irish history. It was definitely something that caught me off guard, too. I was also quick to judge Dracula on its “man’s brain, woman’s heart” narrative, but I definitely think that taking a different approach allows us to see it as a truly feminist novel that fit in well with the Feminism that was rising during its time! It does make me wonder, though, (and maybe I have to go back and reread Kilfeather for the answer), how and why Feminism was so prominent in Ireland versus other countries. Or maybe it was prominent in other places, but because I have tunnel vision for Ireland right now I just can’t see the parallels.

I really liked that you brought in the positive and negative aspects of the female portrayals in Dracula connected to the Irish movement for the right of women to vote. When I first read Dracula, I was unsurprised but a little unhappy with the way that this male author often represented the women in the story as waxing poetic on their instinctual motherly nature or their gentle and tender womanly hearts as inherent nativist to the “female sex,” particularly because he delivered these claims from their own voices rather than his own as a male narrator in the third person, which somehow worsened the effect for me. For a while, it put a damper on my appreciation of the many strengths Mina has throughout the story as a central figure, as you say, almost more important than the men in resolving the problems. I think it is reminiscent of the Suffrage movement at the time period in that it is a process. Just as Constance Markievicz took an active role in the Easter Rebellion, yet other women involved were relegated to “cooks and nurses” (Kilfeather 185). While many aspects of the book can be seen as outdated today, it marks an important shift in representation within a growing literary genre, like Constance’s refusal to be held back by gendered expectations of the era. Smalls steps can still win the race. Stoker’s depiction of “the New Woman” becomes incredibly timely, and different.